“Unexpressed emotions will never die. They are buried alive and will come forth later in uglier ways.”

S. Freud

“Emotion” is a term that came into use in the English language in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as a translation of the French term “émotion” but did not designate “a category of mental states that might be systematically studied” until the mid-nineteenth century. At the same time, many of the things we call emotions today have been the object of theoretical analysis since Ancient Greece, under a variety of language-specific labels such as passion, sentiment, affection, affect, disturbance, movement, perturbation, upheaval, or appetite. This makes for a long and complicated history, which has progressively led to the development of a variety of shared insights about the nature and function of emotions, but no consensual definition of what emotions are, either in philosophy or in affective science.

Emotions are a crucial part of who we are, but they can be messy, complicated, and downright confusing sometimes. Knowing how to name them and talk about them is a key part of developing emotional health.

The simplest theory of emotions, and perhaps the theory most representative of common sense, is that emotions are simply a class of feelings, differentiated by their experienced quality from other sensory experiences like tasting chocolate or proprioceptions like sensing pain in one’s lower back. The great classical philosophers – Plato, Aristotle, Spinoza, Descartes, Hobbes, Hume, Locke – all understood emotions to involve feelings understood as primitives without component parts. An alternative idea was first introduced by William James, who argued that scientific psychology should

stop treating feelings as “eternal and sacred psychic entities, like the old immutable species in natural history”

Emotion is a subjective state of mind. Emotions can be reactions to internal stimuli (such as thoughts or memories) or events that occur in our environment.

It is important to note that emotions are not the same thing as mood. A mood is a state of mind that predisposes us to react a certain way. For example, someone in a low mood is more likely to feel irritated when they trip on a rock. Someone in a good mood is more likely to feel amused by the incident. In general, emotions are reactions to an event, while moods are present before and throughout the event.

Emotions are simply reactions. They by themselves are neither good nor bad.

However, the way we act (or don’t act) on our emotions

can strongly affect our well-being.

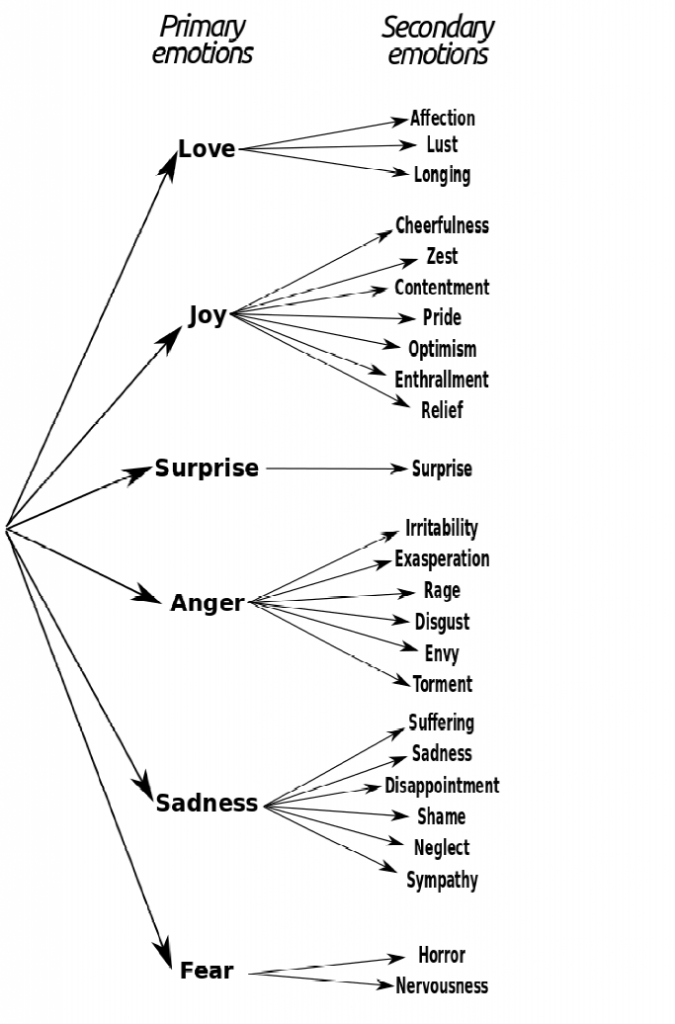

Previously it was understood that there were six different human emotions – happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust. But scientists have now found that there are 27 different categories of emotions. However, Ekman’s concept of five main types of emotion offers a good framework for breaking down the complexity of all the feels.

- Enjoyment – people generally like to feel happy, calm, and good. Enjoyment might be expressed by smiling, laughing, or indulging yourself. The worlds to describe enjoyment: happiness, relief, amusement, love, contentment, excitement, satisfaction, joy, peace, pride, compassion.

- Sadness – everyone feels sad from time to time. This emotion might relate to a specific event, such as a loss or rejection. Sometimes people might have no idea why they feel sad. When a person is sad, they might describe themselves as feeling: heartbroken, disappointed, unhappy, resigned, gloomy, lonely, grieved, lost, troubled, hopeless, and miserable.

- Fear – happens when people sense any type of threat. Depending on that perceived threat, fear can range from mild to severe. Fear can make people feel: doubtful, nervous, terrified, desperate, worried, anxious, panicked, horrified, stressed, and confused.

- Anger – usually happens when someone experiences some type of injustice. This experience can make someone feel threatened, trapped, and unable to defend themselves. Many people think of anger as a negative thing, but it’s a normal emotion that can help you know when a situation has become toxic. Words people might use when they feel angry to include: frustrated, bitter, mad, insulted, cheated, annoyed, peeved, infuriated, vengeful, irritated, and contrary.

- Disgust – people typically experience disgust as a reaction to unpleasant or unwanted situations. Like anger, feelings of disgust can help to protect from things they want to avoid. It can pose problems if it leads someone to dislike themselves. Disgust might cause someone to feel: loathing, dislike, disapproving, horrified, offended, revulsion, nauseated, uncomfortable, disturbed, aversion, and withdrawal.

No aspect of our mental life is more important to the quality and meaning of our existence than the emotions.

Emotions In The Body

A group of brain structures called the limbic system controls our emotions. The limbic system releases chemicals that branch on our emotional states. The type of emotion we feel depends on which chemicals have been released. For example, the hormone oxytocin allows us to experience feelings of love.

Emotions reflect our mental states and also they modify our body chemistry and functioning. For example, when we feel fear, our sympathetic nervous system activates. Our pupils dilate, our heart rate goes up, and we may start sweating. However, equally, our bodily conditions can also affect our emotions. If someone is angry or afraid, they can take deep breaths to activate the parasympathetic nervous system. This system slows your heart rate and helps you calm down.

Why Do We Have Emotions?

Throughout history, philosophers have considered whether humans truly benefit from emotion. There are many cases in which strong emotions cloud our judgment and make us do things we later regret.

Researchers believe humans usually benefit from having emotions. Our emotions motivate us toward certain survival strategies. Each basic emotion had its own purpose. For example, when our ancestors encountered a dangerous animal, fear prompted them to run away to safety. If they come across an obstacle on their way home, anger motivated them to get rid of the problem instead of giving up. And upon arriving safely at home, feelings of joy would reinforce the behaviors that aided their survival.

However, there are times in which emotions cause more problems than they solve. People with clinical anxiety may become paralyzed by fear rather than motivated by it. Individuals with depression can feel so much sadness that they lose the ability to feel joy. Even people without clinical diagnoses can become overwhelmed with emotions.

In many cases, a compassionate therapist can help individuals control distressing emotions. In therapy, individuals can learn how to recognize when feelings are blurring their judgment and bring those emotions down to a manageable level. They may also learn healthy ways to cope with these feelings.

Although there are many different parts of an emotion, feelings are generally considered the most important part.

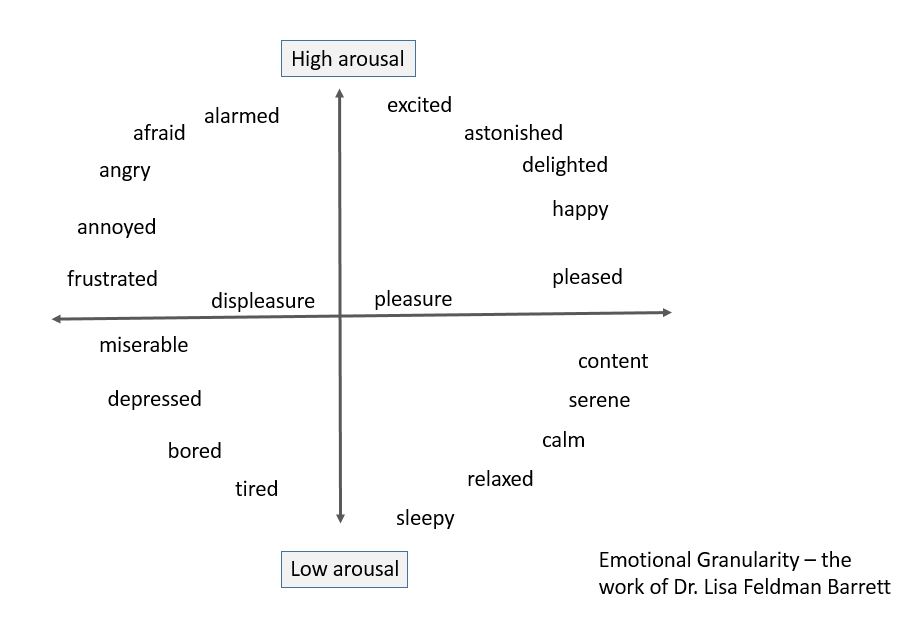

The majority of scientists who study emotion measure it by asking people what they are feeling. It is important to note that terms like “angry” and “amused” might mean different things to different people. Despite these limitations, however, self-reported experience, meaning what a person says about what he or she is feeling, is the most direct way to measure emotional feelings.

- Emotion – Scientists do not always agree on what makes up an “emotion,” but they usually agree that it is more than just a feeling. Emotions can also involve bodily reactions, like when your heart races because you feel excited, and expressive movements, including facial expressions and sounds—for example, when you say “Woah” because you are fascinated by something. And emotions can involve behaviors, like yelling at someone when you are angry. These bodily reactions, expressive movements, and behaviors are often included in scientists’ definitions of “emotion.”

- Feelings – The way that someone experiences an emotion. A feeling is something that you experience internally, in your own mind, and that other people can understand based on your behavior. You can help other people understand how you feel using emotional terms, like “anger” or “sadness” or by using analogies, like “I feel the way a kid would feel if her dad took away her Halloween candy.”

Emotions will always guide you in the right direction!

In psychotherapy emotions are permanent components. Very often people underestimate the power of our emotions and feelings. Lots of people don’t understand their feelings, they don’t know how to read them or what the emotions throughout the body are telling them. When the emotions were repressed for many years and were not acknowledge, it doesn’t mean they went away or disappeared. Our body is storing every single emotion that was not processed by us. Emotions are building up and mixing together within us until we cannot take any more of that until something triggers it. That itself can cause lots of trouble to us, to our physical and mental health.

We are then very often confused and overwhelmed not knowing what is happening to us. Often, in the therapy room, I hear “Am I losing my mind”, “What is wrong with me”, “Nothing happened, so why am I feeling this way”… but only when we slow down and really look at our lives, we then realize how much we went through, how much energy and emotions it involved. Emotions are a great form of communicator, emotions can help us find who we really are, and emotion can help us understand the situations we are in. All we need to do is to start name our emotions, ask ourselves why we feel the way we do… maybe I don’t really like what I am doing -> so why am I doing it? -> To please someone? -> What is in it for me? -> Is it worth it? It is like an internal conversation with yourself. It brings the awareness we need because we then are getting to know ourselves, our needs, and desires. It brings clarity to our actions.

In therapy, when someone comes to me very confused, lost, and distressed we look back at that person’s life. To see what was really going on, what that person went through. Sometimes we have to come back to very painful and hurtful times. And that is okay. That person has the opportunity to re-feel the pain and to name his/her feelings regarding it, in a safe space. That way the repressed emotions are released and the emotions are no longer stored in the body. But it is processed, the length of the process always depends on the individual. And that is what makes us unique, and that is why I love my work so much.

Learning to listen to your emotions rather than being run by them is a superpower!

References:

- American Psychological Association. (2009). APA concise dictionary of psychology.

Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. - (2016). 10 extremely precise words for emotions you didn’t even know you had. The

Cut. Retrieved from https://www.thecut.com/2016/06/10-extremely-precise-words-for-

emotions-you-didnt-even-know-you-had.html - Karimova, H. (2019). The emotion wheel: What it is and how to use it. Retrieved from

https://positivepsychology.com/emotion-wheel - Lomas, T. (2019). Provisional lexicography—By theme. Retrieved from

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332849215_Lexicography_listed_by_theme#pf2f - Nummenmaa, L. Glerean, E., Hari, R., & Hietanen, J. K. (2014). Bodily maps of emotions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,

111(2), 646-651. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/content/111/2/646 - Prinz, J. J. (2007). The emotional construction of morals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Barrett LF, et al. (2007). The experience of emotion. DOI:

10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085709 - Cowen, A. S., and Keltner, D. (2017). Self-report captures 27 distinct categories of emotion bridged by continuous gradients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114 (38), E7900–E7909.

DOI:10.1073/pnas.1702247114 - Russell, J. A. 2003. Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychol. Rev.

110, 145–172. DOI:10.1037/0033-295X.110.1.145

Atlas of emotions

Psychotherapy Kuchenna